Guiding Principles and the status quo

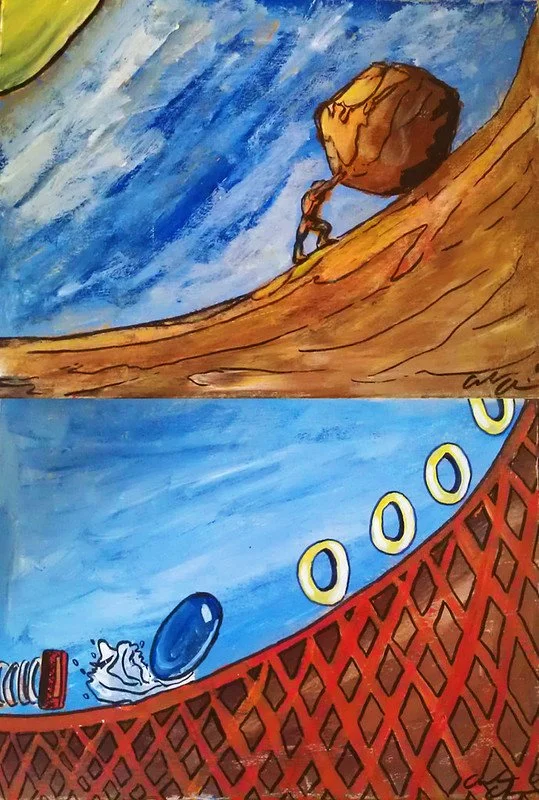

"The Myth of Sisyphus" by aallingh is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

By Jill Hemmington

As part of s. 118 (1) of the MHA there is a contemporary code of practice to guide doctors, approved clinicians, AMHPs and others in relation to hospital admissions, guardianship and community orders. This code needs to include a statement of guiding principles which should inform decisions under the Act (s.118 (2A)) and to which these professionals must ‘have regard’ (s.118 (2D))

The current Code (DoH, 2015) speaks of training requirements to ensure a ‘detailed knowledge’ of the Code, along with its ‘purpose, function and scope’, and knowledge and application of the guiding principles (p.12). It is described as ‘essential’ that all those undertaking functions under the Act understand the principles and ‘always consider’ them when making decisions under the Act (DoH, para. 1.1). Currently, the principles are:

· Least restrictive option and maximising independence

· Empowerment and involvement

· Respect and dignity

· Purpose and effectiveness, and

· Efficiency and equity

The way things are now? There is no formal training and the principles are often disregarded and unenforceable. No relevant professional is required to explain how they have considered and applied the principles to their practice. Anecdotal evidence (data collection lacks the depth and richness of daily AMHP practice) indicates that AMHP reports are not standardised nationally, and not all require details as to how the principles have been applied. The National Workforce Plan for AMHPs states that AMHP reporting ‘should’ (not ‘must’) make clear reference to the principles and how they have been considered, but doctors are not required to record any consideration or application of the principles at any stage. Practice is variable and remains unmonitored, presumably due to their relegated status as mere ‘guidance’.

In the final report of the Independent Review of the MHA 1983, Wessely and colleagues acknowledged the limited awareness of the principles, and that it ‘seems very likely that they do not inform practice in the way they should’. This led to recommendations that the new principles should be the statutory basis for all actions taken under the Act, by placing them at the front of the Act itself and with them governing everything within it. This way, they could be used to hold services to account. The MHA regulations and statutory forms (including reports for tribunals) should be amended to require professionals to record how the principles have been taken into consideration, and to enable local auditing and monitoring as well as CQC’s monitoring and inspection role.

The reforms introduced new principles. ‘Choice and Autonomy’ replaces the current ‘Empowerment and Involvement’ principle. Here, all practicable steps must be taken to support the person to express their will and preferences, and to give this proper weight in decision-making. There should be a mandatory and recorded use of Shared Decision-Making approaches to enable this. The continuing ‘Least Restriction’ principle requires that the Act’s powers are used in the least restrictive and least invasive way. The principle of ‘Therapeutic Benefit’ relates to the effectiveness and appropriateness of treatment and the need for a supportive, healing environment with a view to ending the need to be subject to traumatic coercive powers.

Finally, we will have ‘The person as an Individual’ where care and treatment must respect and acknowledge a person’s qualities, strengths, abilities, knowledge and past experience; and, in particular, respect and acknowledge individual diversity. An underpinning rationale is the longstanding concerns that statutory interventions often do not consider people’s race, culture, identity, disability, place in communities and experiences of discrimination. The review acknowledged the experiences of people from racialised minorities and, with it, the misinterpretations around illness and failure to address negative, stereotypical and stigmatising assumptions about risk. It acknowledged LGBTQ+ groups’ experiences of being stigmatised and misunderstood, and that children and people with learning disabilities receive poor care. So far, so promising.

Yet the Government has made a decision to not place the principles at the front of the Act, nor to amend the MHA regulations and forms to record how the principles have been taken into consideration. The Mental Health Bill, as it stands, does not offer any enforceable requirement to involve people in decision-making, using deliberative ways of supporting service users’ choices (see, for example, Rob Manchester, Watson and Perry and Hemmington). It reads as hospital-centric and, as such, does not directly address the balance with community alternatives to hospital or the essential developments to crisis services. This will also maintain AMHPs’ vulnerability to high levels of moral distress see Hemmington, 2025.

Missing this opportunity to place the guiding principles on the face of the Act will inevitably undermine or render redundant the original purposes of the statutory reforms – including, for the first time, tackling the over-representation of people from racialised backgrounds and the ongoing issue of service users lacking a voice and choice. Without tangible, measurable and enforceable practice changes for all professionals we are left with the status quo. Having mandatory, recorded guiding principles is surely the only means by which we will achieve the necessary focus on these essential areas of practice, and deliberate, deliberative attempts to challenge and address longstanding problems.

By the way, whatever happened to Respect and Dignity?