CTOs: “Should they stay or should they go?”

"The Clash : Train In Vain" by Howdy, I'm H. Michael Karshis is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

By Alan Bristow

“It's always tease, tease, tease…..”

Reading over our mini blog series and the other editors’ comments, I’m inclined to agree with one of the prevailing themes. The 2025 amendments (now in statute as of the 18th December 2025) feel like something of a missed opportunity. And, there is no better case for this than with a certain section of the Act that has long been in the crosshairs for reform or, indeed, outright abolition; Community Treatment Order’s (CTOs) (s.17a) introduced during the last round of amendments in 2007. Initially designed to reduce the number of admissions for the so-called ‘revolving door’ patient and to improve community engagement, they have since proved divisive and achieved a position of some notoriety - to say the least.

Although CTOs had a significant amount of airtime in parliament during the bill’s multiple readings, and although progressive changes to CTO criteria and usage were prominent throughout the debates and the bill’s many revisions, by the time Christmas ’25 came and went, the far-reaching reforms many thought were afoot seem to have dissipated almost entirely.

True enough, the language around the criteria for CTOs has altered and Tribunals now have additional powers in recommending that a particular condition be removed. However, given the underlying principles guiding the amendments (choice & autonomy, therapeutic benefit, least restrictive, person as individual), and the tantalizing prospect during the early days of the bill that CTOs might be done away with altogether, it is curious that we have now ended up here. I say this, as of all the many elements to MH legislation that could have been altered, reformed or removed, surely it was high time for a radical rethink concerning the legal basis underpinning s.17a?

For is there a more contentious and ethically suspect area of the Act than CTOs? Consent to treatment for ECT possibly? Or perhaps the current redefinition of psychiatric disorder excluding learning disability? All worthy entries. Yet, CTOs are likely to feature near the top of the grievance list many professionals have with modern MH legislation. Again, once more, we find AMHPs ideally placed to comment. Anecdotally, many AMHPs I speak with often say something similar to the effect that CTOs are bureaucratic or overly draconian. Or that they are utilized to manage inpatient anxieties rather than to promote individualized treatment, are largely ineffective clinically, and are a burden in terms of professional time and effort. But what of the research picture? Although fragmentary and far from systematic, it would suggest, likewise, that CTOs are troublesome. Barkhuizen et al (2020) have identified that those on CTOs are generally readmitted sooner and spend more time in hospital, yet interestingly they also tend to have a lower mortality rate. Burns et al (2013) found that the imposition of compulsory supervision does NOT reduce the rate of readmission for psychotic patients. Burns (2008) similarly provides robust arguments for the overall ineffectiveness and possible ethical dilemmas CTOs raise. Indeed, issues abound with CTOs the further into the research literature one goes. DeRidder et al (2016) identify that despite accumulating evidence that CTOs do not, on the whole, improve outcomes, psychiatric opinion in using them has not shifted since their implementation. It would appear that CTOs are controversial, problematic and potentially at odds with their original stated aims.

Yet, if we consult Stroud et al (2015) we find that service users themselves have reported that their CTOs can indeed be helpful and advantageous, especially in terms of the ‘containing’ element they bring to care planning. Stroud states that service users self-report the positive structure and support CTOs can provide. The picture, as ever, is complicated. There are clearly undoubted serious implications in terms of human rights (Right to Private Life - Article 8 HRA) and social justice with regard to long term restrictions for individuals in the community. In fact, the contentious nature of CTOs has been recognized by central Government who, in 2018 published their Independent Review (and precursor to the bill), Modernising the Mental Health Act. The review stated unequivocally “that rates of detention were rising and that CTOs were being used much more widely than the government had anticipated when they were introduced by the 2007 act.” The review further added that “if the success of CTOs is measured by reducing the number of people readmitted to hospital, there is limited evidence to show this goal has been achieved” (House of Commons Library, MH Research briefing, 14/05/25).

In short, CTOs have been recognized to be problematic both in terms of their increasing numbers and overall clinical effectiveness. To make matters worse, the disproportionate use of CTOs for certain racialised communities was strongly emphasized throughout the review and made its way into much of the language and debate accompanying the bill’s long and winding route through parliament. For instance:

• In 2020-21, 6,070 new CTOs were reported which was a 31% increase compared with 4,650 CTOs reported in 2019-20. Before this spike, the number of CTOs was relatively stable at 4,810 on average (from 2016/17 to 2019/20). In 2024-25, NHS digital reported 6,575 new CTOs.

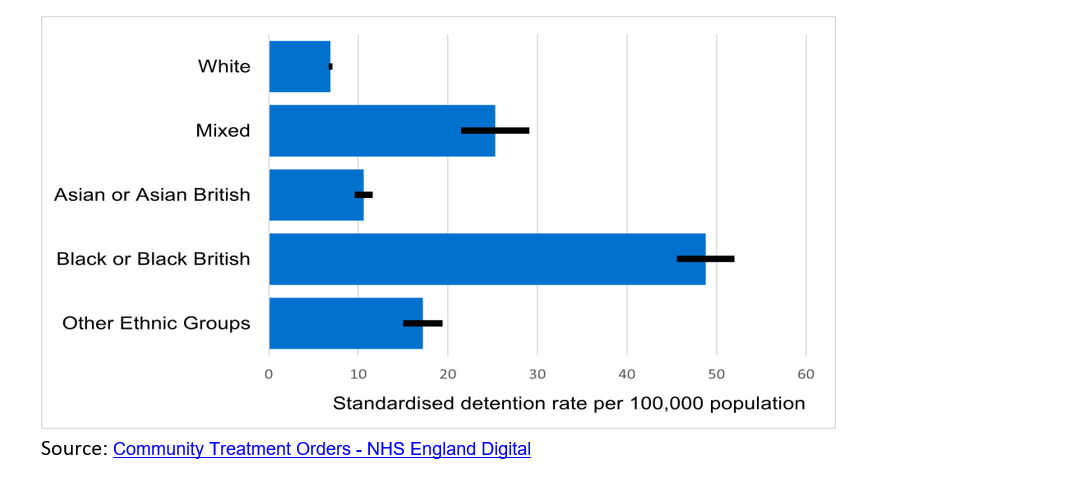

• Amongst broad ethnic groups, CTO use is highest for Black or Black British people (61.3 uses per 100,000 population). This is over eight and a half times the rate for the White group (7.5 uses per 100,000 population). See accompanying graph:

The most pressing and obvious response to this would be to question the worth in retaining CTOs at all within MH Law and policy. Indeed, when legal reform of the MHA 1983 started to really gather pace, this was precisely what was suggested. A joint committee recommendation from late in 2022 stated that there was “not enough evidence to demonstrate benefit” and that “CTOs should be abolished for patients under part II of the MHA” (see para 68 Joint Committee Report 2022-2023). The government's response to the joint committee was to similarly agree whilst acknowledging there may still be a role for them in respect of part III restricted patients. (Recommendation 12-Government response to the Joint Committee on the draft Mental Health Bill - GOV.UK.) What’s more, the abolition of CTOs in their entirety is something that further aligned with a broad section of opinion emanating from the service user movement, MH charities and think tanks (see, Our position on Community Treatment Orders (CTOs) & Mental Health Act reform | Mind). A clear case, one would have thought, for the inevitable demise of S.17a.

However, this initial radical approach to removing S.17a from law was quickly dropped. Why? No doubt due to a variety of factors including feasibility, a mixed or incomplete research picture, and suggestions that, in certain cases, they can be clinically beneficial. However, following a series of tragic events in Nottingham and Southport, (as well as the media’s response to subsequent Governmental inquiries focusing heavily on MH concerns) one can't help but feel that law-makers may have been discouraged from removing any and all legal mechanisms for recalling high risk community patients back into hospital from the Act. In fact, CTOs, or the lack thereof, featured prominently in the independent investigation into the care and treatment of Valdo Calocane (See, Independent investigation into the care and treatment provided to VC). Whatever the case, until quite late on in the bill’s hearing, a raft of changes to CTO usage and implementation were still being proposed which were designed to address these wide-ranging concerns. Although abolition of CTOs was eventually consigned to the scrapheap, three main areas of reform emerged and, for all intents and purposes, were widely believed to be the future of s.17a. These related to;

• a 12-month time limit (renewable by a registered psychiatrist and consultation with the patients ‘nominated person

• Inclusion of the risk of ‘serious harm’ to patients or others within the criteria for CTO usage.

• Identification of the ‘therapeutic benefit’ a CTO can provide.

(see, Get in on the Act: Mental Health Act 2025 | Local Government Association)

The most noteworthy change here being the 12-month maximum time limit. A compromise or watering down of the initial abolitionist position. Presumably designed to reduce the numbers of CTOs and instances where they are used or renewed unnecessarily, it originated with Lord Scriven and his amendment to clause 6 of the bill which would have ensured that, “a community treatment order shall have a maximum duration of 12 months, subject to provisions.” Those provisions being that, “the responsible clinician may extend the duration of a community treatment order beyond 12 months only after consulting the patient, the patient’s nominated persons, and any relevant mental health care professional involved in the patient’s treatment or care planning.” (see, Amendment 11 to Mental Health Act 2025 to Mental Health Act 2025 - Parliamentary Bills - UK Parliament) So, a 12-month time limit, but one that would have been extendable provided everyone agrees, or provided everyone has been consulted?! Not too difficult to see the potential ineffectiveness of this measure. If it would have only required the agreement of the NP and ‘any relevant’ MH professional, it is hard to envisage how this too would have had any significant impact on overuse. In the end, this was also swiftly abandoned and sent on its way to the dustbin of potential statutory changes. The story of CTO reform begins with the eyebrow-raising notion of abolishing CTOs altogether, only soon to be forgotten in favour of a lengthy flirtation with the idea of a ‘12-month maximum’. But one, likewise, proving to be nothing other than a tease given its omission from statute just prior to the bill receiving royal assent.

“If they go there will be trouble, if they stay it will be double……?”

So what did we get? Well, the two-part test that must be fulfilled to meet the criteria for detention. Those two stages being;

“1) Serious harm may be caused to the health or safety of the patient or another person, if they are not detained or made subject to a CTO; and

2)The decision maker must consider the nature, degree and likelihood of the harm, and how soon it would occur.

No doubt the concept of ‘serious harm’ will require time, case law and significant use in practice before we get a workable, robust and clinically effective notion that can be argued, debated and defended in Tribunals, courts, care planning procedures and so on. For those of us looking ahead to a newly devised code of practice, serious harm’ will be one of the first things consulted. But until a workable definition of ‘serious harm’ is introduced then my feeling, much like with the newly devised guiding principles concerning ‘therapeutic benefit,’ is that this amounts to little more than a tinkering with language, and one that is clearly subject to wide interpretation.

Lastly, an unexpected gift for all to ponder was the puzzling inclusion of the designation, mandate, role or title of ‘Community Clinician’. Fellow Critical AMHP’s feast your eyes on clause 21 which states:

the Act to require the community clinician responsible for overseeing the patient’s care as a community patient, to be involved in decisions regarding the use and operation of CTOs. This covers the decision to make a person subject to a CTO, to vary or suspend conditions made under a CTO, to recall to hospital a patient subject to a CTO, and to revoke a CTO after a patient has been so recalled.

And that,

Subsection (2) amends section 17A(4) of the Act, to require that, where the responsible clinician is not the clinician who will have care for the patient in the community after discharge, then that community clinician must also agree in writing that the CTO criteria are met. This achieves two aims – continuity of care of the patient from the hospital into the community and additional professional oversight (see, Mental Health).

So, the completely new designation of the ‘Community Clinician’ who appears to be none other than the regular Responsible Clinician (RC) who happens to be placed in the community. Essentially, the Approved Clinician (AC) who would oversee the patient's care if they were to become a community patient. But, as you may have already fathomed, any patient subject to a CTO is of course already a community patient and would presumably therefore have an identified AC/RC in an outpatient setting? So, this ‘new’ title only refers to the already existing community RC. The idea that this individual would NOT be ‘involved in decisions regarding the use and operation of CTO’s’ for patients they ‘will have care for’ seems bizarre if not outright negligent.

What the new amendments do, however, is put a legal onus that the Community Clinician be consulted before an RC adds, varies, or suspends discretionary conditions. Likewise, the Community Clinician must also be consulted before an RC recalls, revokes, or discharges a CTO. However, in cases where the RC is also the community clinician, (which I tentatively suggest will be in most cases) then this clause and the inclusion of the Community Clinician seems like something of a moot point. Who else would be adding, varying, revoking, or discharging CTOs? This feels, on first reading, like an unnecessary confusion and complication of terms. Perhaps the real benefit here is really in respect of ensuring lines of communication between inpatient services and community teams are strengthened via the statutory obligation for hospital RC’s and outpatient RC’s to be simultaneously involved in any CTO arrangement and that this must be ‘in writing.’

The question then as to ‘whether CTOs should stay or whether they should go’ has clearly been answered by the government. They are staying and there's not a huge amount of difference to them. The initial revolutionary zeal to abolish CTOs supported by swathes of service user experience and opinion, professional concerns, MH charities and think tanks has been fudged resulting in a thinly, watered down version of the progressive changes initially suggested and no doubt required.

In closing, perhaps the biggest lost opportunity relates to the disproportionate use of CTOs for certain racialised groups. Quite how any of these amendments concerning the criteria, nominated person or inclusion of the community clinician will address the shameful discriminatory and unethical usage of CTOs nationally is not immediately evident. It's hard to argue against a renewed focus on improved communication between wards and community teams and surely there can be little issue with the ‘tightening’ of the criteria. But, with so many glaring problems with s.17a in terms of their uneven application, ethical implications and suspect clinical utility, the MHA amendments of 2025 have not gone nearly far enough. History would suggest the law is always late to catch up. MHA amendments circa 2045 anyone?

References

Barkhuizen et al, (2020) “Community Treatment Orders and association with readmission rates and duration of psychiatric admission: A controlled electronic case register study" in BMJ Open.

Burns, T. Lawton-Smith, S & Dawson, J. (2008) “Community Treatment orders are not a good thing" in the British Journal of Psychiatry. September 2008.

Burns, T. et al (2013) “Community Treatment orders for patients with psychosis: A Randomised controlled trial" in Lancet. Vol. 381, Issue 9878. p.1627-1633

DeRidder, R. et al (2016) “Community Treatment Orders in the UK 5 years on: a repeat national survey of psychiatrists”. In BJ Psych Bulletin 40 p.119-123.

Stroud, J et al (2015) "Community Treatment Orders: learning from experiences of service users, practitioners and nearest relatives" in Journal of Mental Health. 24 p.88-92.